AUTHOR: Muriëlle van Hagen

With 103 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants — 6,369 in total — El Salvador was, in 2015, and had been for many years, one of the most violent countries in the world.

The roots of this violence trace back to the civil war between 1980 and 1992, during which more than 75,000 people were tortured, extrajudicially executed, or forcibly disappeared. In the years that followed, gang violence claimed thousands of lives.

In March 2022, after 87 people were killed in a single weekend, President Nayib Bukele declared a state of emergency. He launched a war on gangs and within just 21 months, more than 73,800 people were arrested. The country changed dramatically: homicide rates and other crimes dropped significantly. Streets once considered too dangerous became liveable again. Many Salvadorans now praise and thank President Bukele for restoring safety to their country.

But is there another side to this story? What lies behind the mass arrests, and what happens behind the closed doors of one of the world’s largest prisons? Above all: how well are human rights protected under this ongoing state of emergency?

A significant driver of violence over the past decades has been the conflict between two gangs: Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18. Both originated in Los Angeles and were mostly formed by Salvadoran migrants who had fled the country during the civil war. After the war ended, many gang members were deported back to El Salvador by U.S. authorities. Once returned, the violent conflict between the two gangs escalated, eventually gripping the country and creating one of the most dangerous environments imaginable. People lived in constant fear of being extorted, kidnapped, raped, or murdered.

When Nayib Bukele became president in 2019, he expressed a commitment to promote, defend, and respect human rights. At the time, many international human rights violations were already taking place in the country. In March 2022, after more than 80 homicides in a single weekend, Bukele announced the state of emergency to combat gang violence and restore safety. Many believe this spike in violence was the result of a broken secret deal between Bukele’s government and the gangs, which allegedly involved reducing homicides in exchange for certain benefits for gang leaders, such as access to social services in areas under their control. It was initially meant to be a month-long state of emergency, but it has been repeatedly extended ever since.

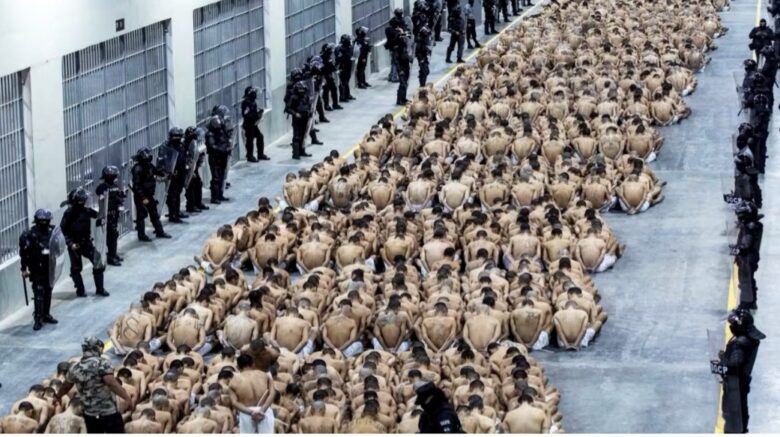

So far, the state of emergency has led to the detention and arrest of tens of thousands of individuals. Over 1.5% of the population is now imprisoned, many under arbitrary detention, often without clear evidence or proper investigation. Daily arrest targets imposed on police and military pressure them to detain people based on anonymous accusations, physical appearance (such as tattoos), or residence in marginalized communities. This violates the right to a fair trial and the presumption of innocence. Many detainees are unaware of the charges against them and lack access to effective legal defence. Mass virtual trials are conducted by anonymous judges who can try up to 500 people at once, often with little or no evidence. Pre-trial detention has been legalized, resulting in individuals being held for months without a court ruling.

Prison conditions are extremely concerning. Facilities are overcrowded and lack adequate food, clean water, sanitation, and medical care. Reports of torture, abuse, and degrading treatment are widespread. Over 300 people have died in custody, with families frequently left uninformed. Cases of enforced disappearances have also been reported. The government has shown a lack of transparency, has failed to investigate these deaths, and has not taken sufficient measures to prevent further abuses.

The state of emergency remains in place to this day, and President Bukele shows no signs of stopping it anytime soon. While his numbers proudly show a decline in crime rates and an increase in public safety, one must ask: what is the value of safety if human rights are repeatedly violated? Behind the statistics are countless innocent people affected, many already burdened by the country’s violent past. If the state of emergency continues like this, the question is no longer whether human rights will be violated, but how many more innocent people will become victims of human rights abuses. Saving a country from gang violence is necessary, but doing so at the expense of human rights is never justifiable.

Sources (article):

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/08/eviscerating-human-rights-el-salvador-gang-problem/

https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/AMR2974232023ENGLISH.pdf

https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-briefing-notes/2023/03/el-salvador-state-emergency

Sources (pictures):

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nayib-Bukele

https://news.sky.com/video/el-salvador-thousands-of-gang-members-transferred-to-mega-prison-12821402